September 26, 2025

Basho Haiku Walkway #04

Basho’s Journey in Three Scenes

The journey through Basho’s haiku is more than just a walk across landscapes; it’s a passage through history, memory, and timeless emotions. In this edition, we visit sacred sites in the Tohoku region—Chuson-ji, Hiraizumi, and Sendai—where Basho’s verses captured both fleeting beauty and echoes of the past. Each haiku reveals a moment where nature and human destiny quietly meet.Haiku 10. Location: Chuson-ji, Iwate Prefecture

5月雨の 降りのこしてや 光堂

Early summer rains—

yet leaving untouched in light,

the Golden Hall

Behind the Haiku - Discover the hidden stories behind each haiku -

1. The setting: Chuson-ji and the Golden Hall (Konjikido)Chuson-ji, a sacred temple in Iwate, is home to the renowned Golden Hall, also known as the Konjikido. Built in the late Heian period, its interior and exterior were lavishly decorated with gold leaf, a brilliant symbol of Buddhist paradise and the enduring legacy of the Northern Fujiwara clan. When Basho arrived centuries later, the hall still shone with reverence amid surrounding decay.

2. The seasonal rains (samidare)

The word samidare refers to the persistent rains of the fifth lunar month, when early summer showers fall in abundance. These rains often blur landscapes, soaking everything without exception. Yet here, Basho suggests, the Golden Hall appears to resist their reach, as if untouched by the season’s downpour.

3. A contrast between impermanence and permanence

Rain embodies transience and decay, a constant reminder of nature’s impermanence. The Golden Hall, glittering against this backdrop, symbolizes spiritual continuity and human devotion that endures through the centuries. The juxtaposition of fleeting rain and eternal gold deepens the scene's poignancy.

Basho’s vision

This haiku isn’t just about weather or architecture but about time itself. Basho marvels at how a sacred creation can shine through ages, even as the world is repeatedly washed over by the rains of impermanence. The verse captures a subtle harmony: the flow of nature and the enduring nature of faith.

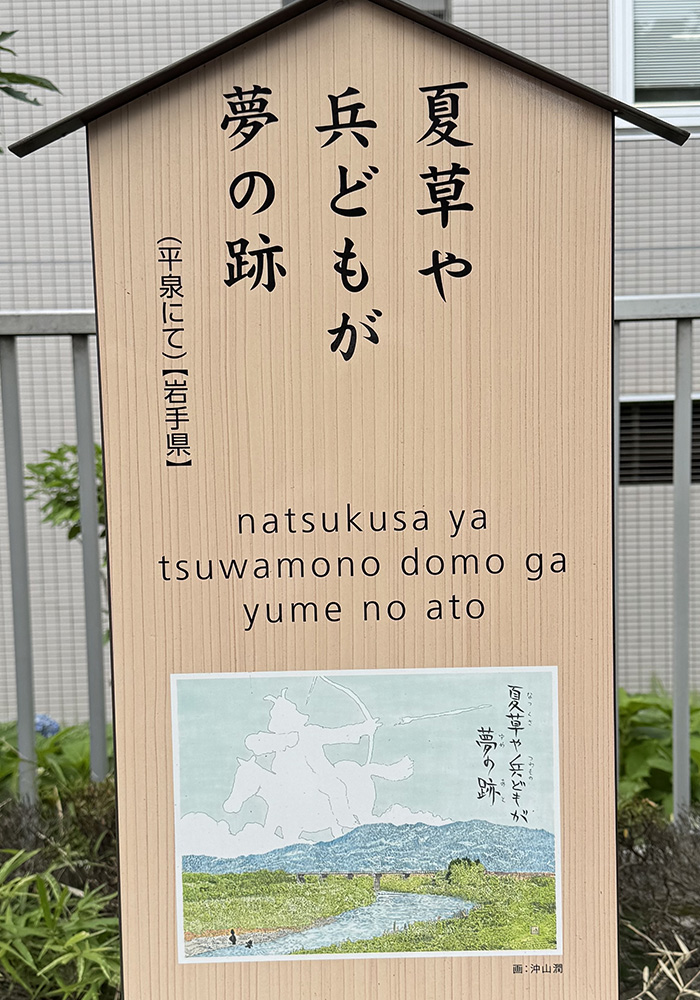

Haiku 11. Location: Hiraizumi, Iwate Prefecture

夏草や 兵どもが 夢の跡

Summer grasses—

all that remains

of warriors’ dreams

Behind the Haiku - Discover the hidden stories behind each haiku –

1. The setting: Hiraizumi and the fall of the Fujiwara clanHiraizumi, once a thriving political and cultural hub under the Northern Fujiwara, rivaled Kyoto in grandeur. Its palaces and temples represented power and elegance. By Basho’s era, however, this splendor had long faded. Standing on these ruins, he faced the silence where armies once marched and courts once flourished.

2. The summer grasses (natsukusa)

The image of thick summer grasses is more than just seasonal scenery—it represents nature’s reclaiming of human ambitions. Where warriors once fought and died, plants now grow freely, indifferent to past glories. The grasses symbolize both the cycle of renewal and the inevitability of forgetting.

3. Echoes of warriors’ dreams

The “dreams” (yume no ato) allude to the vanished aspirations of samurai and leaders. Their victories, struggles, and even tragedies have dissolved into memory, leaving only faint traces. The haiku compresses centuries of history into a single, haunting image of emptiness overgrown with life.

Basho’s vision

This verse stands as one of Basho’s most profound meditations on impermanence. By evoking the silence of ruins covered in grass, he contrasts the transience of human power with the quiet persistence of nature. It is at once elegiac and universal—a reminder that all worldly ambition fades, leaving behind only the soft whispers of time.

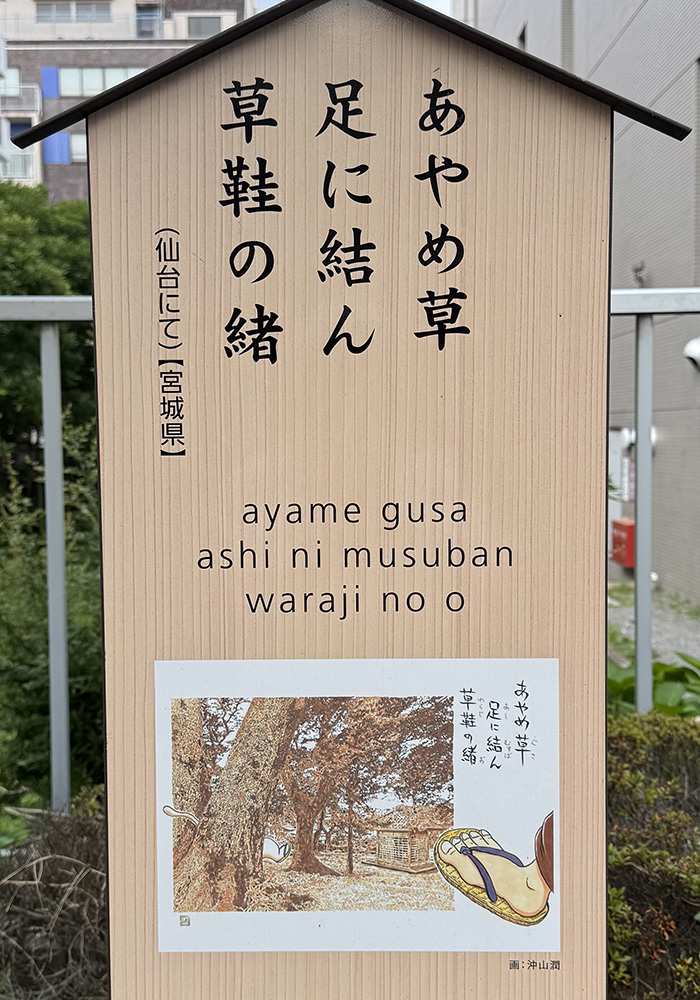

Haiku 12. Location: Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture

あやめ草 足に結ん 草鞋の緒

Iris blossoms—

tying sandal straps

around my feet

Behind the Haiku - Discover the hidden stories behind each haiku –

1. The setting: Sendai and Basho’s journeySendai, the castle town of the powerful Date clan, was an essential stop for Basho as he traveled north. Here, amid the bustle of the city and the surrounding countryside, Basho paused to capture a quiet, personal moment before resuming his long journey on foot.

2. The iris (ayamegusa)

The iris, blooming in early summer, was prized for its elegant form and seasonal beauty. In classical poetry, it symbolized both grace and travel, as its name was often linked to words for “path” or “road.” Encountering irises at this moment tied Basho’s own wandering steps to centuries of poetic tradition.

3. The act of tying sandals (waraji no o)

The simple gesture of fastening the straw sandal straps before walking further becomes a symbolic act. It grounds the traveler in both the physical reality of the journey and the poetic atmosphere of the season. By linking this humble action with the sight of blooming irises, Basho elevates an everyday necessity into a moment of beauty.

Basho’s vision

This haiku blends the practical and the poetic: the hardships of constant travel softened by the grace of seasonal flowers. In tying his sandals amid blooming irises, Basho wove his own life into nature’s fabric, affirming that even small acts can resonate with elegance and meaning. The verse captures the spirit of a traveler whose path is illuminated by fleeting yet timeless encounters.Next in the Journey

Basho’s footsteps will soon guide us from Tohoku into the heart of the northern Kanto region, where new encounters await along the ancient roads:- Haiku 13 — Shinobu-no-Sato, Fukushima Prefecture

- Haiku 14 — Kurobane, Tochigi Prefecture

- Haiku 15 — Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture